We want to reduce rather than replace the amount of waste humans are generating.

Sneh Bangar, Clemson researcher

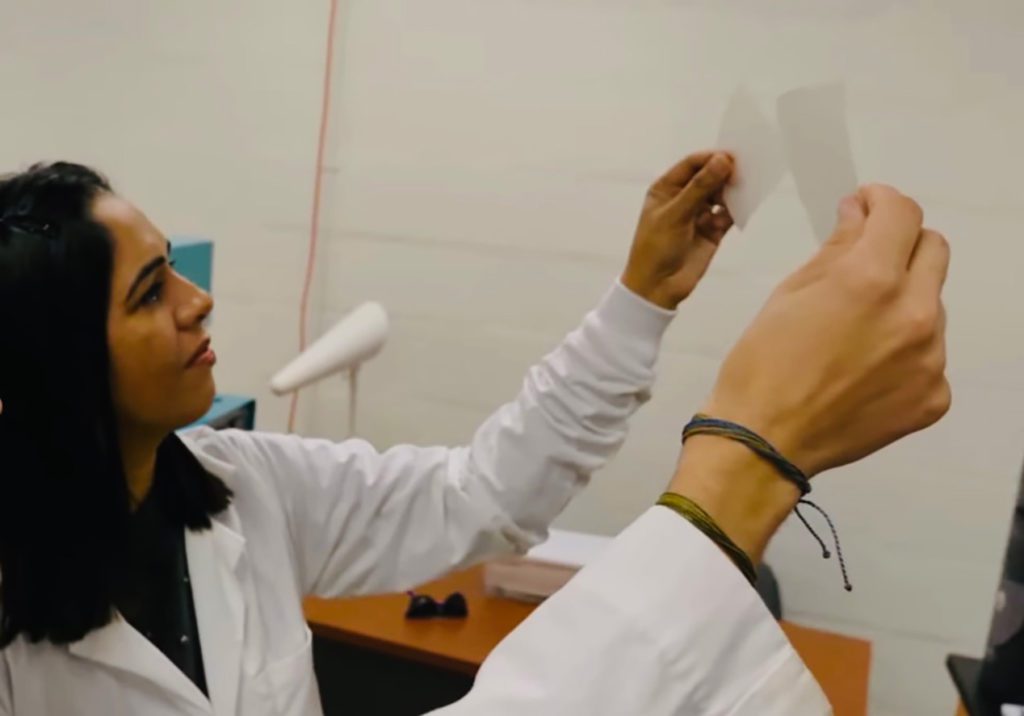

A Clemson University postdoctoral researcher believes she has found a way to use kudzu to create a biodegradable food packaging film as an alternative to plastic.

Sneh Bangar, who graduated from Clemson with a doctoral degree in packaging sciences in December 2022, hopes her research will lead to the use of pearl millet starch and plentiful kudzu vines to put a dent in the roughly 400 million tons of plastic waste produced on Earth each year.

Her dissertation – Development, characterization and application of pearl millet starch-based nanocomposite films reinforced with kudzu cellulose nanocrystals – describes a process to create a biopolymer-based film called Biopack from pearl millet starch reinforced by kudzu weed cellulose nanocrystals.

Biopack is a starch-based film designed to be used once and then to biodegrade.

“The accumulation of plastic waste has created serious human, wildlife and environmental problems,” Bangar said. “Because of increasing consumer consumption, post-consumer packaging has become a major source of plastic waste. There is a great need to develop alternative packaging materials which are environment-friendly, economical and effective.”

Her research uses cellulose nanocrystals from kudzu to reinforce pearl millet starch-based biopolymer films. Pearl millet is a warm-season crop grown throughout the United States for animal feed and fodder. About 70% of each pearl millet grain is starch, which is a renewable, natural and biodegradable polymer.

Starch-based films have some practical limitations, including poor processibility, limited strength and limited high-water absorption capabilities, but modifications can be made to overcome these constraints.

When making starch-based film, starches are reinforced with natural fibers, such as cellulose, a complex carbohydrate that comprises about 33% of all vegetable matter. Humans cannot digest cellulose, but animals such as cows and horses can.

“Cellulose is the most abundant renewable natural polymer on earth,” Bangar said. “Using cellulose nanocrystals to reinforce starch improves functionalities of starch-based films. This research is important because not much work has been done to explore the cellulosic fibers of weed species such as kudzu.”

Kudzu is a weed found throughout most of the southeastern United States. Some estimates suggest it may cover 7.4 million acres in the South.

Kudzu grows well under a wide range of conditions and in most soil types. Although it has been found as far north as Pennsylvania, kudzu grows best where winters are mild, summer temperatures are above 80 degrees and annual rainfall is 40 inches or more. It is a vigorous weed that can grow enough to smother out neighboring plants or trees. Vines can also cover nearby structures, utility poles, farm fences and more. In addition, kudzu can create environmental problems such as shading out native species in forest understories, altering soil chemistry and decreasing native biodiversity.

Kudzu control is expensive and can take several years to manage. Michael Marshall, Clemson Cooperative Extension Service weed scientist, said herbicides – imazapyr and glyphosate – most often are used to manage kudzu. But this is not an easy task.

“The taproot of each kudzu plant can be up to 7 inches in diameter and 6 or more feet in length,” said Marshall, who is stationed at the Edisto Research and Education Center in Blackville, South Carolina. “These massive storage roots are why kudzu is difficult, almost impossible, to control once established.”

Because kudzu grows abundantly throughout the South and is difficult to control, Bangar believes it would be beneficial to explore new ways to use the plant. Her lab is the first to isolate nanocrystals from kudzu to develop starch-based films reinforced with kudzu cellulosic fibers. In addition to cellulosic fibers and starch, the packaging material also contains clove bud oil.

Bangar used this film to store grapes in a cold setting. After 15 days, she found the grapes had maintained their weight, firmness and soluble solids. Soluble solids in grapes include sugars, organic acids, phenolic compounds, nitrogenous compounds and structural polysaccharides. Total soluble solids are used to estimate grape quality.

“This suggests starch-based films reinforced with kudzu cellulosic fibers and clove bud oil have the potential for commercial packaging of foods during short storage periods without affecting food quality and sensory attributes,” Bangar said.

The best way to dispose of Biopack is by composting. Biopack is designed to completely degrade within 3-4 weeks of disposal. It is designed to degrade into water and provide natural nourishment to the environment. If put into waste bins, the packaging will biodegrade on its own.

As she continues her research, Bangar is focused on developing Biopack for commercial use. Her hope is the product will be used to reduce plastic waste.

“Currently, the cost to commercially develop this biodegradable film is more expensive than plastic,” she said. “But we will continue our study. We hope to produce a film that can coexist with current manufacturing operations. Our focus is to develop active packaging films for wider market acceptability. We want to reduce rather than replace the amount of waste humans are generating.”

Bangar studied for her doctorate under the guidance of Clemson professor William Scott Whiteside. In addition to her dissertation study, Bangar also has participated in other food packaging research. A catalog of articles about her research can be found at https://bit.ly/Bangar_Research.

-END-

Bangar is a starch-based film designed to be used once and then to

biodegrade and provide natural nourishment to the environment.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu