Penn State’s College of Agricultural Sciences researchers have created a film by bonding an antimicrobial layer to conventional, clear polyethylene plastic typically used to vacuum-package foods such as meat and fish. The researchers believe the findings could be of interest to the packaging and muscle food industries, as well as regulatory agencies that seek to reduce pathogens in the food supply.

The antimicrobial lining of the film comprises a pullulan-based biopolymer produced from starch syrup during a fermentation process, which is already approved for use in foods. Pullulan, a water-soluble “polysaccharide”, is essentially a chain of sugar, glycerin and cellulose molecules linked together. To kill pathogens such as Salmonella, Listeria and pathogenic E. coli, researchers infused the pullulan with Lauric arginate, made from naturally occurring substances and already approved for use in foods.

The pullulan film slows the release of the antimicrobial, disbursing it at a predictable rate to provide continuous bacteria-killing activity, explained researcher Catherine Cutter, professor of food science. She added that without being impregnated into the film, the antimicrobial would run off the surface of a food product, such as meat, or evaporate.

Lauric arginate was chosen as the antimicrobial because it is a broad-spectrum antimicrobial compound that proved highly effective in killing and limiting the growth of pathogens that cause foodborne illness, noted Cutter, assistant director of food safety and quality programs for Penn State Extension.

Cutter’s research group in the Department of Food Science has been experimenting with antimicrobial films made of pullulan for a decade. But she credits Abdelrahim Hassan, who spearheaded the latest study, for devising a procedure to fuse the pullulan-based antimicrobial layer to the polyethylene plastic — allowing the novel composite to be born. Hassan, who was a visiting scholar in Cutter’s lab when the research was conducted, is an associate professor of food safety and technology at Beni-Suef University in Egypt.

“Hassan figured out a way to get the pullulan to attach to polyethylene,” Cutter said. “He modified the formulation of pullulan and changed the hydrophobicity of the plastic. These steps were important because polyethylene repels everything — nothing sticks to it. So, the challenge was, how could we get pullulan to adhere to it.”

Before settling on Lauric arginate, the researchers experimented with other food-grade antimicrobials incorporated into the antimicrobial layer such as thymol and nisin. The antimicrobial activity of the resulting composite films was evaluated against cocktails of Shiga toxin-producing E. coli, Salmonella spp., Listeria monocytogenes and Staphylococcus aureus.

“Films containing nisin were ineffective; thymol disrupted some pathogens but not others; and Lauric arginate inhibited the growth of the four types of bacteria,” Hassan said.

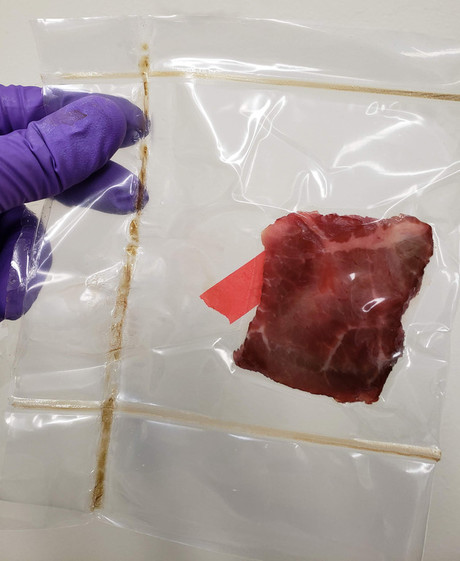

Based on these preliminary results, Shiga toxin-producing E. coli, Salmonella spp., Listeria monocytogenes and Staphylococcus aureus were experimentally inoculated onto raw beef, raw chicken breast and ready-to-eat turkey breast, vacuum packaged with the composite antimicrobial film, sealed and placed into refrigerated storage for up to 28 days.

In findings published on 20 January 2020 in the International Journal of Food Microbiology, Hassan and Cutter reported that the composite antimicrobial film containing Lauric arginate significantly reduced foodborne pathogens on the experimentally inoculated surfaces of the raw and ready-to-eat muscle foods after refrigerated storage.

Future research in Cutter’s lab will evaluate how the composite antimicrobial film affects the shelf life of food products, and investigate consumer perceptions and acceptability of the novel film.

This research was partially funded by the US Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture.