1

SHARES

Despite a public outcry following Blue Planet 2 in 2017, single-use plastic is still ubiquitous in the UK. It is almost impossible to avoid, whether for food, healthcare or endless online deliveries. But is plastic as bad as we think? Anna Proffitt explains the importance of full disclosure to tackle this emotive subject.

Plastic serves an important purpose that is often overlooked by the public: protecting the food that has a significantly higher carbon footprint than the packaging that contains it. There is a fine balance between reducing plastic and not increasing food waste.

We are right to be concerned about our overall plastic use (five million tonnes in the UK) and to call on retailers and manufacturers to do more. In recent years we have seen examples of the absurdity of overpackaging, particularly for goods that have their own natural packaging such as citrus fruits. It must be emphasised, however, that not all packaging is created equal – the argument for wrapping coconuts in film hardly stacks up against using fully recyclable trays to deliver fresh protein.

Unnecessary single-use plastic rightfully has its critics and is part of the ‘throwaway’ society. Despite people’s fears over changing habits and practicality issues, the 5p plastic bag charge and plastic straw ban are examples where common sense has prevailed.

Global and national initiatives have sought to tackle the issue. In the UK, WRAP’s Plastics Pact has turned the goals laid out in the global Ellen MacArthur Foundation New Plastics Economy initiative into industry-friendly goals and campaigns for consumers. Launched in 2018, over 120 companies have signed up; it would thus be unfair to say that companies are not taking action, but we could be doing more.

Food waste vs plastic waste

Packaging is a far more complex issue than is portrayed by the media. There are good reasons for using plastic to protect food: it is lightweight, hygienic, durable and resistant. It is also low cost and easy to manufacture at scale. Its airtight seal led to the creation of Modified Atmosphere Packaging (MAP) and vacuum packing (VP), which has increased shelf life far beyond what was historically possible.

MAP and VP have enabled producers to sell fresh meat more safely and with a longer shelf life, by inhibiting microbial spoilage and maintaining product structure, integrity and taste. Even with refrigeration, fresh cut meat may typically only last a few days before becoming microbiologically unacceptable. Innovative plastic packaging, however, has enabled prolonged shelf life for weeks at a time, facilitating a reduction in food waste along the supply chain, from transportation to storage, retail and in-home. Many alternative processing methods are available and frequently used to produce a variety of products; however, some can depreciate the value of meat. To enable producers to cater to demand, both fresh, frozen and preserved products must be available to consumers.

Unnecessary single-use plastic rightfully has its critics and is part of the ‘throwaway’ society.

The meat industry faces ever harsher scrutiny over its environmental credentials, so it is paramount that production efficiency is maximised, with minimal waste along the supply chain. Plastic has helped improve this enormously and shall continue to do so.

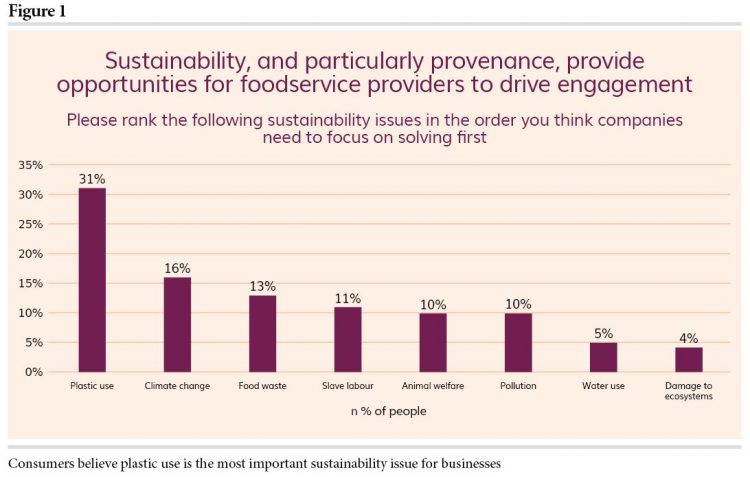

Public opinion has changed significantly in recent years. A study by AHDB (Figure 1) showed that of eight sustainability issues consumers thought businesses should focus on, plastic use was the most important. In third place was food waste. Research like this highlights the importance of getting the right message across regarding plastics; the two issues are inextricably linked.

Plastic as a renewable resource

Despite plastic’s bad reputation, its aforementioned benefits mean most companies are still using it, while taking reasonable measures to improve it. Monoplastics are both recyclable and can be made from recyclate. Most UK domestic recycling streams allow mainstream plastics to be widely kerbside-recycled; the UK recycled over one million tonnes of plastic in 2017, which equates to 46.2 percent1 – up from 25.2 percent in 2012.2 If materials such as paper or card were used, it is unlikely they would have been recycled – soggy, stained paper would have been removed from the stream as ‘contaminated’.

Plastic keeps our food fresh, prolonging shelf life, and is very useful in the meat industry

A variety of materials and methods for using recycled plastic to wrap food are approved and used. This approach contributes more to a circular economy than a material that may have initially superior environmental credentials but lacks any ‘afterlife’ and hence ends up in landfill. With constant pressure to reduce plastic in systems where it is not yet possible, using recycled plastic is a more sustainable alternative. Unfortunately, however, this material (especially food-grade) is in high demand, outstripping supply and forcing the price up. The Plastic Tax proposal for 2022 is supposedly designed to push companies to increase their recycled content. This will put further pressure on the recyclate material price.

With low supply and inconsistent recycled raw material, the challenge of consistent packaging output is especially pertinent for a large supplier/retailer. Allowing a little flexibility can overcome this. For example, Waitrose announced that its ready-meal trays will vary in colour, depending on the ingoing recyclate at the time of manufacture.3

The free market PRN system

Packaging Recovery Notes (PRN/PERNs) were launched in 1997 through the Producer Responsibility Obligations Regulations. The ‘free market’ trading scheme allows for PRNs to be created in evidence of a processor recycling material, which are then traded and sold to obligated companies (such as packaging packers/fillers). All stakeholders along the supply chain theoretically contribute to the costs of recycling the product they helped to produce.

The meat industry faces ever harsher scrutiny over its environmental credentials, so it is paramount that production efficiency is maximised, with minimal waste along the supply chain…

Free market forces shocked the system in 2018 when China closed its doors to waste imports, leaving the UK supply of PRNs low, yet the demand consistently high. The result was a jump in PRN price from £80 to £450. At the time of writing, the PRN price is 432 percent higher than at the same time last year. The factors affecting the PRN price are complex, but high prices are likely to have a longer-term impact on FBOs material choice (the paper PRN price is £4.95). The biggest concern for many businesses is transparency and accountability for PRN spending. Without this, it is hard to account for the money paid through the scheme and see obvious improvements in our recycling systems.

The disjointed recycling infrastructure in the UK has impeded companies’ efforts to produce suitable packaging and created confusion for consumers. Cash-strapped councils struggle to meet demand and the public expect more: 83 percent of adults believe not enough is being done to encourage people to recycle.4 It is therefore more important than ever to ensure the money generated through PRNs is used effectively to support a circular economy.

What can we do?

We can, of course, promote over-the-counter protein sales. Bring-your-own-tub policies (trialled by Morrisons and Waitrose) would reduce plastic waste, but an unmodified pack atmosphere will compromise shelf life and likely lead to higher food waste – there is no magic wand.

Some industries have better options than others: in May 2019, Fyffes announced they had developed a recyclable paper ‘loop’ to hold a bunch of bananas – a positive step forward. However, in comparison, fresh protein presents more significant challenges.

Fierce competition within the packaging and protein sectors means research and development is usually confidential, but encouragement of collaboration and a pre-competitive approach may boost the sector and help to find technical solutions.

Government support is essential to drive change in the industry. Companies need approval for materials or processes related to food contact materials. Post-Brexit, approvals may no longer be the domain of EFSA, but instead the UK Government. They must apply resource, expertise and pace to keep up with business needs. Research costs can be very high, and new products/materials are commonly more expensive than the original. Government investment in material science research and shelf-life testing would be a real boost to progress.

Educating the consumer beyond the oversimplified media message that ‘plastic is bad’ is also fundamental. WRAP do great work educating the consumer, but they are only impactful to those who are listening. YouGov found that 83 percent of people think paper bags are better for the environment than plastic bags5 – context is clearly key. Differentiating between plastics, their uses, and not demonising necessary plastic is important to bring a sense of balance to the issue.

Conclusion

A balance must be struck between reducing plastics and increasing food waste. As an industry, meat processors not only have a legal duty to protect consumers through food safety measures, they also have an obligation to produce the highest quality product with the longest shelf life. Indeed, the progress the industry has made in the last century is in part due to plastic.

Government support is essential to drive change in the industry.

The conversation needs to turn from a simple demonisation of plastic, to how we maximise resources to become increasingly efficient and remodel our food and packaging systems into a circular economy. The fundamental message is that all stakeholders in the supply chain must collaborate to help build more effective solutions – a circular economy cannot be created by one company or local authority alone.

Research, collaboration and government authorities taking pragmatic approaches to find solutions is the best way forward. Transparency over money generated through PRNs should improve the way it is invested. There are no easy answers, but by working together we can help tackle the plastic problem.

References

1. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/…

2. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data….

3. https://www.retailgazette.co.uk/blog/…

4. https://d25d2506sfb94s.cloudfront.net…

5. https://yougov.co.uk/topics/health/…

About the author

Anna Proffitt joined the BMPA as Technical Policy Manager in April last year. She attended Harper Adams University and studied Food and Consumer Studies BSc (Hons). Previous experience includes Commercial in horticulture, Compliance (food safety) in retail, and Management in the hospitality industry.