Advertisement

Kurbo by WW promises to fight childhood obesity by teaching kids aged 8 to 17 healthy eating strategies — but is it ever a good idea to teach kids how to diet?

By Virginia Sole-Smith

This story was originally published on Aug. 16, 2019 in NYT Parenting.

In her before photo, Vanessa, 8, is a smiling and slightly round-bellied little girl. In her after photo, she stands taller and slimmer, hand on hip. According to the website for Kurbo by WW, a new health app for children, Vanessa’s body mass index dropped by 11 points under the program’s guidance.

“I’m amazed at how strong-willed and motivated she is,” the site quoted Vanessa’s mom as saying of her daughter. “When she sets a goal, she doesn’t break it. I see that she feels better about herself.”

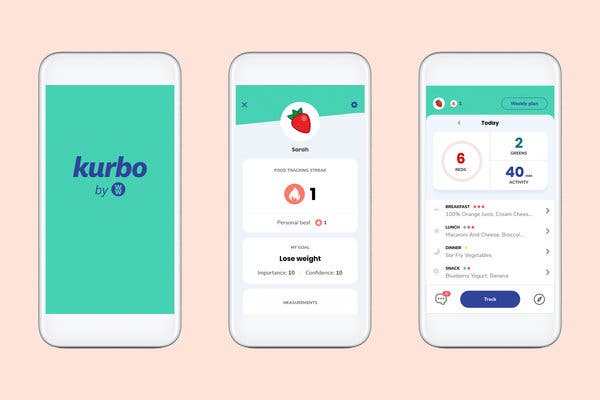

Weight Watchers, a veteran diet industry company that’s been around since 1963 and which recently rebranded as WW, acquired Kurbo Health, a technology start-up in Palo Alto, Calif., in August 2018. Last week, they released Kurbo by WW, a free mobile app for kids between ages 8 and 17, who can enter their height, weight, age and health goals, and then track what they eat and how much they exercise. The program also offers a virtual health coaching service for a fee.

Though WW is billing the app as focusing on healthy eating rather than on weight loss, its launch prompted a backlash on social media last week, as thousands of users — including eating disorder researchers, therapists, dietitians, pediatricians and former dieters — voiced their concerns.

Anna Sweeney, R.D., a dietitian in private practice in Concord, Mass., tweeted Wednesday: “The majority of eating disorder clients that I work with have had a history of dieting. For most, it started with Weight Watchers.”

As of Saturday morning, more than 30,000 people had signed a Change.org petition, urging the company to remove the app.

The launch comes at a time when many are squaring their own feelings with the ways that focusing on what they eat has negatively impacted their relationships with food and their bodies. At the same time, parents are wondering whether their children need to slim down. One in five children and adolescents living in the United States are classified as obese, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And while experts agree that the increasing body weights of young Americans is a serious public health concern, they worry that telling children that they need special diet and exercise interventions might perpetuate stigma about larger bodies, and that an app that encourages kids to track their food intake might lead some to develop disordered eating and unhealthy relationships with food.

Which brings up an overarching question: Should kids want or need to lose weight? And how young is too young to be watching what you eat?

Jennifer Harriger, Ph.D., an associate professor of psychology at Pepperdine University who studies the development of weight stigma and disordered eating in children and adolescents, said that there’s strong evidence that dieting at any age, but especially in early childhood, can increase the risk of anorexia, bulimia and binge eating later on.

In a study published in the journal Pediatrics in 2003, for instance, researchers from Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard University periodically surveyed the eating habits of 8,203 girls and 6,769 boys between ages 9 and 14 between 1996 and 1999. While both boys and girls reported dieting in some capacity during the study period, about twice as many girls — nearly 30 percent — did so, and were five to 12 times more likely to have reported binge eating than those who didn’t diet. The girls who dieted were also more likely to have gained weight by the end of the study. In another study published in 2012, researchers from the University of Minnesota and Columbia University analyzed surveys that 1,902 adolescents took between 1998 and 2009, starting when they were in middle or high school. The adolescents who reported skipping meals or using other unhealthy weight control behaviors such as using food substitutes or taking diet pills in the early years of the study were nearly twice as likely to gain weight than the non-dieters.

In recent years, Weight Watchers has worked to overhaul its image, presenting itself less as a scale-obsessed giant of modern diet culture and more as a lifestyle program that approaches “wellness” more holistically. Weight loss meetings are now called “wellness workshops,” and their “WW Freestyle” program promises weight loss by eating from a preapproved list of foods rather than by counting points. “Our brand has evolved,” said Gary Foster, Ph.D., a clinical psychologist and obesity researcher who serves as WW’s chief science officer. “For 50-plus years, we were known as Weight Watchers, and while we’re proud of our legacy, that had some unintended consequences.”

While Foster said that the company as a whole will certainly help those “who want and need” to lose weight, he was quick to emphasize that Kurbo is “not prescribing weight loss to kids.”

But some experts disagree. “Diets don’t call themselves diets anymore — they’re all wellness systems or lifestyle plans,” noted Anna Lutz, M.P.H., R.D., a pediatric dietitian in Raleigh, N.C., who specializes in eating disorders and family feeding. “But when a child is asked to use an app like this, they get the message that their body is flawed and they need to use external rules to restrict and change their body in order to be accepted. This pressure can be spoken or unspoken and have the same impact.”

In 2016, the American Academy of Pediatrics released a report that advised parents and doctors to avoid discussing weight or prescribing weight loss to children and adolescents over concerns that it could increase their risk of developing disordered eating habits or weight gain. As NYT Parenting has previously reported, young children are especially susceptible to such conversations, which can later manifest as low self-esteem and unhealthy body image.

“Focusing on weight loss in young people is misplacing our priorities,” said Traci Mann, Ph.D., a professor of social and health psychology at the University of Minnesota who studies health behaviors like dieting. She noted that “everyone, regardless of weight” can benefit from adopting healthful habits like eating more fruits and vegetables and getting more sleep and physical activity. Whether these activities lead to weight loss is irrelevant, Dr. Mann said, as long as they’re healthy.

When using the Kurbo app, children are not asked to count calories or cut certain foods as they would with a traditional diet. But it does ask them to enter their weights and the foods they eat each day, which are then categorized according to a Stanford University-developed “traffic light system,” which aims to help kids discriminate between healthy and unhealthy foods. Over time, the idea is that they’ll eat fewer of the foods from the app’s unhealthy (or “red light”) list and more from the healthy (or “green light”) list. When they hit their weekly exercise and eating goals, they’re rewarded within the app.

Fruits, vegetables and low-calorie items like vinegar, skim milk and seltzer water are classified as “green light” foods, according to Kurbo, and kids can eat as much of them as they want. “Yellow” foods, such as chicken, pasta or lowfat milk are to be consumed moderately. A “red light” food — which includes cake, candy and chips, but also foods that many parents would consider healthful like whole milk, sourdough bread and peanut butter — means kids should “stop and think how to budget them in.”

There are, however, potentially confusing distinctions; “cheese” is defined as red, for example, but “cheese sticks” are yellow. The app also asks kids to estimate portion sizes, so eating just one-fifth of an avocado is considered yellow, but if you eat three-fifths or more, it moves to red.

To Joanna Strober, a technology investor and entrepreneur who co-founded Kurbo Health in 2014, simply being more aware of “red” foods can help children become more discerning and nutrition-savvy eaters. “Kids hear that junk food is bad, but they don’t understand what junk food is. They think bagels and cream cheese are a healthy breakfast or that juice and protein bars are healthy, and they’re really surprised to learn these are red,” she explained. “Or they’ll tell us, ‘everything on my school lunch tray is red!’”

But Lutz said that grouping foods into “good” and “bad” categories might confuse kids further, since many of the red light foods are ones they’ve been taught by caregivers to trust and enjoy, which could make them anxious.

It also may lead some children to track their intake obsessively, or cut out certain food groups altogether. When restricting certain foods becomes difficult to sustain, they may rebel and resort to hoarding food, a problem that Strober acknowledged her health coaches have encountered in some families who used Kurbo before WW’s acquisition.

Lutz teaches parents to model healthful eating by serving family meals and by encouraging kids to listen to their hunger and fullness cues rather than following strict food rules. “Young children are concrete thinkers. Adults can understand this abstract idea of red, yellow and green foods, but children interpret it rigidly,” she explained. “They’ll think if eating less red foods is good, then eating no red foods is even better.”

Kurbo’s health coaches are trained to contact a child’s parents if they notice signs of disordered eating, or if a child reports losing more than two pounds per week in a two-week period.

But Lutz and others said they hope Kurbo would look more closely at how even subtle pressures around food and body weight may fuel a child’s body anxieties, especially as they approach puberty. “I recognize that the creators of this app state that it’s not a diet,” Harriger said. “But they ask children to input their height and weight into the app. They track food intake and exercise behaviors and weight loss is a goal. How is this not a diet?”

[For more on healthy eating, see our tips on how to foster healthy eating habits in young children and how to plan family meals.]

Virginia Sole-Smith is a journalist, author of “The Eating Instinct: Food Culture, Body Image and Guilt in America,” and co-host of the Comfort Food Podcast.