0

SHARES

With multiple forces acting against global food security, researchers in Singapore have been innovating. Read their solutions that help combat food waste and obesity, while improving health and sustainable food production.

The global food crisis marches closer. Droughts and floods caused by climate change are threatening our ability to produce enough food for a growing global population. According to Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates, crop yields could fall by up to 25 percent by 2050.

Aside from this impact, the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted supply chains which has also impacted food security. This has led to shortages in all manner of foodstuff from poultry to palm oil, as well as escalating food prices.

Geopolitical tensions and conflicts add to this growing food insecurity by limiting access to energy, creating rising inflation and debt.

At the same time, almost one-third – 1.3 billion tonnes – of the food produced for human consumption is wasted or lost every year, according to the United Nations. And all the while obesity rates are alarmingly high: 1.9 billion adults are overweight or obese according to the World Health Organization.

Against this backdrop, NTU researchers have devised innovative solutions so that we can provide for a sustainable future. They support the university’s commitment to mitigating our impact on the environment, which is one of four ‘humanity’s grand challenges’ that NTU has identified and seeks to address through its NTU 2025 strategic plan.

Fermenting food waste to produce food

Edible by-products from food manufacturing are a potential resource that can be tapped to sustainably increase food supply, reduce obesity and reduce food waste. Two such by-products are okara, the insoluble remains of soybeans from the production of soy milk and beancurd, and brewer’s spent grain, consisting of residual barley pulp from the beer industry.

Consisting mainly of soybean fibre, okara is rich in protein and nutrients such as carbohydrates. About 1.4 billion tonnes of okara is produced around the world each year, mostly by Asian countries, including Japan, Korea, China and Singapore.

Similarly, brewer’s spent grain is high in protein and fibre. Beer is the fifth most consumed beverage across the globe, the production of which creates approximately 39 million tonnes of spent grain each year.

With the help of microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi, the nutritional profile of okara and brewer’s spent grain can be increased.

Okara

In a study published in LWT – Food Science and Technology in December 2021, okara fermented with a mixed culture of the fungus Aspergillus oryzae and the bacterium Bacillus subtilis, commonly used to make soy sauce, was found to have the best total dietary fibre profile and highest content of phenolics – compounds with antioxidant properties.

“Fermentation is a way to repurpose okara, a major food manufacturing side stream that is often discarded, and transform it into a highly nutritious food,” said Dr Ken Lee, senior lecturer at NTU’s School of Chemistry, Chemical Engineering and Biotechnology, who led the study.

Dr Lee’s research has also shown that fermented okara can be used to combat obesity. In a collaboration with Waseda University in Japan, okara from Sing Ghee Beancurd Manufacturer, a leading producer of beancurd in Singapore, was fermented with the fungi Aspergillus oryzae and Aspergillus sojae, which are used to make soy sauce and miso. The findings of the study showed that after three weeks, rats that were fed a diet supplemented with the fermented okara gained the least weight, compared to rats given normal and high fat diets. They also had less visceral and subcutaneous fat and lower triglyceride and cholesterol levels.

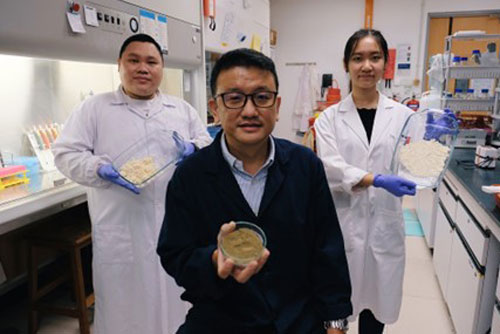

(From left) NTU PhD student Ferdinandus, NTU senior lecturer Dr Ken Lee, and NTU PhD student Ng Li Shiuan, part of the research team that developed the fermented okara that can combat obesity

Spent grain

Likewise, fermented spent grain can be made into a protein-rich food emulsifier. And, unlike commercial food emulsifiers from egg yolk, this novel emulsifier is derived entirely from plants.

In a study led by Professor William Chen, Director of NTU’s Food Science and Technology Programme, the product was made by extracting and drying proteins from the fermented grain.

The resulting plant-based emulsifier can replace dairy and eggs in condiments such as mayonnaise, salad dressings and whipped cream.

Compared to the store-bought version, mayonnaise produced with the plant-based emulsifier contained more protein and higher amounts of some essential amino acids as well as antioxidants.

The mayonnaise prepared with the NTU emulsifier also tasted identical to off-the-shelf mayonnaise, yet had improved texture and spreadability.

“Upcycling food waste such as spent grain for human consumption is an opportunity for enhancing processing efficiency in the food supply chain, as well as potentially promoting a healthier plant-based protein alternative to enrich diets,” said Prof Chen.

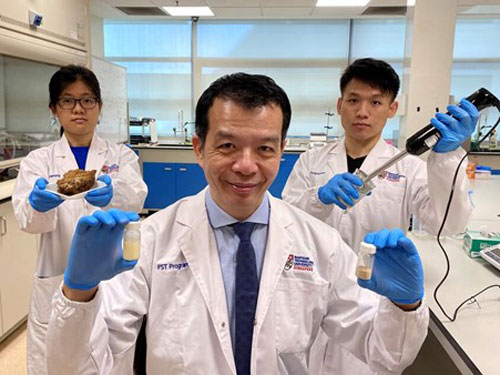

(From left) PhD student at NTU’s Food Science and Technology Programme, Ms Chin Yi Ling; Prof William Chen, Director of NTU’s Food Science and Technology Programme and Dr Josh Chai, research fellow at NTU’s Food Science and Technology Programme, who developed the plant-based food emulsifier from fermented grain. Credit: NTU Singapore

Food from unconventional sources

Besides turning food waste into food, alternative sources of food and ingredients may help to ease pressure on their supplies when they are disrupted. They may also reduce the negative environmental effects created by the conventional manufacture of these food products.

Meaty alternative

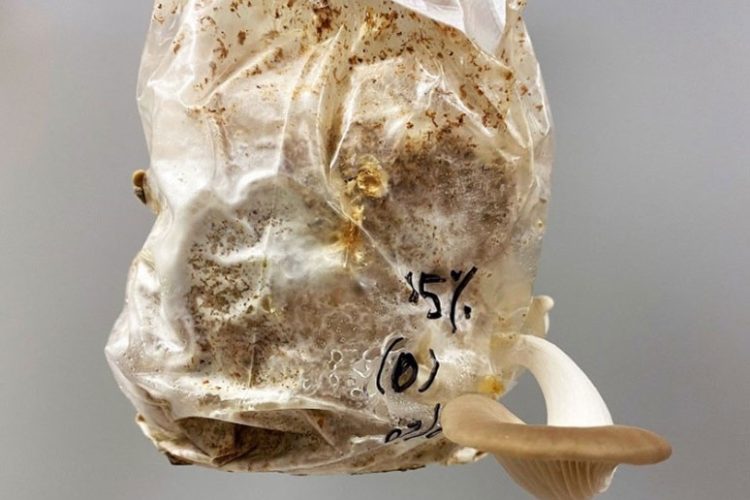

Recently, Prof Chen and his team have developed a nutritious fungi-based food product that resembles meat. The fungus Agaricus bisporus used to cultivate the product is the same one that grows button mushrooms. Grown on nutrient-rich common food waste such as soybean skin, wheat stalk and brewers’ spent grain, NTU’s fungi-based food product tastes more like meat and has a better nutritional content than proteins from peas, chickpeas, wheat gluten and soy.

The fungi-based food product that resembles meat was grown from the same fungus that produces button mushrooms. Credit: NTU Singapore

Palm oil is the most widely consumed vegetable oil, found in many food products, ranging from chocolate to cooking oil.

However, the rapid expansion of oil palm plantations has been implicated in massive deforestation in several countries, destroying the habitats of endangered native wildlife.

Earlier this year, disruptions in palm oil production as a result of labour shortages from COVID-19 restrictions also resulted in soaring prices and a shortfall in production.

To alleviate these shortages, edible oils that can replace palm oil are being explored.

Microalga oil

In one study led by Professor Chen, a common microalga Chromochloris zofingiensis was cultivated and edible oils were extracted from it.

The oil extracted from microalgae is a healthier and greener alternative to palm oil. Credit: NTU Singapore

The findings of the research were that oil derived from the microalgae was healthier and more eco-friendly than palm oil. It contains more polyunsaturated fatty acids than palm oil, which can help reduce ‘bad’ cholesterol levels in blood and lower a person’s risk of heart disease and stroke.

The microalgae-produced oil developed in collaboration with scientists from the University of Malaya, Malaysia, also contains fewer saturated fatty acids, which have been linked to stroke and related conditions.

As the microalgae grow, they convert carbon dioxide to biomass relatively quickly. Hence, the scientists say that using microalgae to produce edible oil would also help remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, as the microalgae can convert it to biomass and oxygen via photosynthesis.

Prof Chen is currently working with local and international food companies to bring these food innovations from the laboratory to the market and onto our plates. Watch this space.