“If during the next sixty to seventy years the world farmer reaches the average yield of today’s US corn grower, the ten billion will need only half of today’s cropland while they eat today’s American calories,” concluded agronomist Paul Waggoner in his seminal 1996 article, “How Much Land Can Ten Billion People Spare for Nature?“

In their 2013 article, “Peak Farmland and the Prospect for Land Sparing,” Waggoner and Rockefeller University researchers Jesse Ausubel and Iddo Wernick citing current global trends in yield increases and fertilizer deployment calculated if biofuel production could be reined in, that as much as 400 million hectares (1.5 million square miles) of current cropland could be returned to nature by 2060. That’s about 25 percent of the land currently devoted to growing crops. “Now we are confident that we stand on the peak of cropland use, gazing at a wide expanse of land that will be spared for nature,” the authors concluded.

It is worth noting that according to Food and Agricultural Organization data, cropland has not yet topped out, but agricultural land which includes pastures peaked back in 2000.

Now a new study in the journal Nature Sustainability by researcher Christian Folberth and his colleagues at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Austria reinforces the findings from these earlier reports.

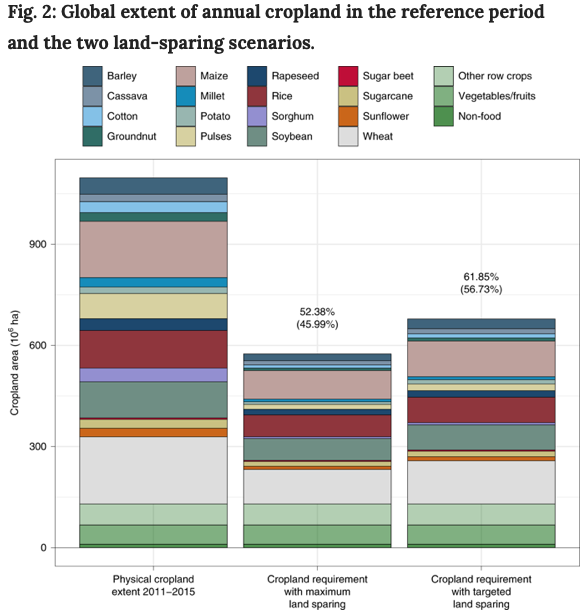

In their article, “The global cropland-sparing potential of high-yield farming,” the researchers calculate a scenario that closes current global yield gaps, bringing the crop yields of farmers in poorer countries up to those in richer countries. Achieving that goal “would allow reduction of the cropland area required to maintain present production volumes by nearly 50% of its current extent.” That would mean that about 576 million hectares (2.2 million square miles) could be restored to nature.

The researchers also sketch out an alternative high crop yield scenario that specifically aims to protect and expand the habitats of threatened species. In that case, cropland use would still shrink by almost 40 percent.

Keep in mind that these scenarios are conservatively reckoning what would happen to global land use assuming that essentially all of the world’s farmers adopt modern high yield agriculture. They do not take into account technological improvements in farming over the coming decades.

In addition, possible shifts in consumption toward alternative protein sources such as plant-based “meats” or cultured meats are not considered. Since about 36 percent of cropland is used to produce animal feed and the vast majority of agricultural land is pasture, such changes in consumer tastes could result in hundreds of millions more hectares of land being spared for nature by the middle of this century.

At the end of my book The End of Doom, I wrote:

New technologies and wealth produced by human creativity will spark a vast environmental renewal in this century. Most global trends suggest that by the end of this century, the world will be populated with fewer and much wealthier people living mostly in cities fueled by cheap no-carbon energy sources. As the amount of land and sea needed to supply human needs decreases, both cities and wild nature will expand, with nature occupying or reoccupying the bulk of the land and sea freed up by human ingenuity. Nature will become chiefly an arena for human pleasure and instruction, not a source of raw materials. I don’t fear for future generations; instead, I rejoice for them.

Happily this new study bolsters that conclusion.