Advertisement

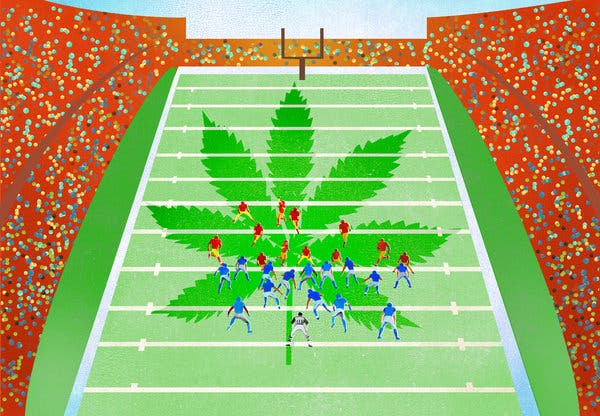

The league’s new labor agreement eased rules about players’ use and caught up with many sports that had already liberalized their policies.

The 10-year labor agreement between the N.F.L. and players union that was ratified on March 15 is filled with dozens of incremental changes, most notably the one-percentage-point increase in the share of league revenue that the players will receive.

One of the biggest overhauls in the agreement, though, was a change the league had long resisted: loosening the rules governing players’ use of marijuana.

Under the new collective bargaining agreement, players who test positive for marijuana will no longer be suspended. Testing will be limited to the first two weeks of training camp instead of from April to August, and the threshold for the amount of 9-delta tetrahydrocannabinol — or THC, the psychoactive compound in marijuana — needed to trigger a positive test will be raised fourfold.

In adopting the changes, the N.F.L., a league not known for its liberal views, caught up to and in some ways leapfrogged Major League Baseball, the N.B.A. and other leagues that had already eased their rules as acceptance of marijuana became more common in many parts of the country.

“There is a generalized sense that the fans don’t care about the issue, so it’s possible to appear progressive,” said Paul Haagen, co-director of the Center for Sports Law and Policy at Duke University.

N.F.L.’s laxer standards are a big departure from the past. But while players will not be suspended for positive tests, they can be fined several weeks’ salary, depending on the number of positive tests. First-time positive tests will, as before, mean diversion into a league-mandated treatment program. Players who refuse to take part in testing or clinical care can be suspended for three games after a fourth violation, with escalating penalties for further violations.

Current and former players have long pushed for looser restrictions on marijuana, which they claim is a less addictive pain reliever than prescription medication, and a growing number of N.F.L. owners saw the rules as a hindrance because resulting suspensions kept some of their best players off the field.

Over the years, the N.F.L. had resisted loosening its marijuana rules to avoid conflicting with federal and state laws. But as more states have approved the use of marijuana for medical or recreational purposes, the league found itself enforcing a policy that, in some instances, was more punitive than local laws. In 11 states, including seven with N.F.L. franchises, the drug is legal for any use. Thirty-one states allow use for medical reasons. The Green Bay Packers and the Tennessee Titans play in states where marijuana remains entirely illegal.

The N.F.L. and the N.F.L. Players Association continue to study the purported healing and addictive qualities of marijuana. The players pushed for a relaxed marijuana policy in part because of mounting research that details the hazards of alternatives — including the addiction rates among prescription opioid users and the irreversible internal damage that can be caused by opioids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as Toradol, which has long been used to treat N.F.L. players.

“The league’s considerations included a number of issues, including its status legally, but most important was always the advice and recommendations of the medical and clinical professionals,” Brian McCarthy, a league spokesman, said. That “remains the case.”

It is unclear what percentage of N.F.L. players use marijuana. Over the years, current and former players have estimated that 50 percent to 90 percent of players use the drug. Former players like Ricky Williams and Rob Gronkowski have openly discussed the benefits of marijuana and cannabidiol, or CBD, a nonintoxicating compound found in the plant. But it wasn’t until 2016 that the first active player — Eugene Monroe, an offensive lineman with the Baltimore Ravens — urged the league to stop testing players for marijuana so that he and others could take it to treat chronic pain.

Now out of the league, Monroe said that the N.F.L. and union had not gone far enough in the new agreement. “Why are they still testing at all?” he said. “I don’t understand. Just move on from this and do the right thing and let the players make the choice. There’s no secret that players smoke marijuana.”

The new rules will not change the status of players who are currently suspended for violating the substance abuse policy that is being replaced. Players who were banished under the previous agreement, after multiples positive tests, must still petition Commissioner Roger Goodell to be reinstated.

For example, Cowboys defensive end Randy Gregory, who has been suspended four times for missed or failed tests, has asked to be reinstated after being suspended indefinitely in February 2019, according to ESPN.

Some current players said that the looser testing standards were irrelevant, because they did not use the drug. “No lie i could care less about the marijuana policy,” Quandre Diggs, a defensive back with the Seattle Seahawks, wrote on Twitter about 10 days before the agreement was ratified.

Some former players warn that the looser rules could lead to a spike in drug abuse. Randy Grimes, who played 10 seasons for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers and now works as a substance abuse counselor after a long battle with opioid addiction, said that the N.F.L. must do more to address the mental health problems that drugs both mask and amplify.

“The marijuana now is incredibly engineered and potent, and it’s trouble waiting to happen,” he said. “I’m in the industry that sees the danger of mood-altering substances, and that’s what marijuana is.”

The trend in professional sports, though, is to reduce penalties. In December, Major League Baseball removed marijuana from its list of banned substances and now treats it the same way as alcohol: Players are not randomly tested unless they are in a treatment program. The National Hockey League still tests for marijuana, but there is no punishment for a positive result. Players with “a dangerously high level” of THC in their system are referred to the player assistance program for evaluation.

N.B.A. players must take four random tests for marijuana during the regular season. After a first positive test, a player must enter a drug program. A second positive test will result in a $25,000 fine, and a third will lead to a five-game suspension.

While the N.F.L. Players Association hailed the looser standards as a victory, they were also a win for the owners. In the making of this new labor deal, the relaxation of the testing rules may have been one of the easiest points to negotiate.

The owners prioritized economic issues, like the split in revenue and the addition of extra games, over rules governing the workplace. Players sought to gain ground on those issues, demanding things like less taxing training camps and limits on the number of full-contact practices.

The owners saw loosening the testing standards as a concession that might persuade some players to vote for the agreement, which ultimately passed by just 60 votes.

“The owners were able to get two things done at the same time by minimizing the penalties and appealing to another segment of the membership,” said Charles Grantham, the director of the Center for Sport Management at Seton Hall University who was a longtime executive at the National Basketball Players Association. “They found religion because it was cheap and easy. It wasn’t a big give.”