These days, everyone is slinging a bread recipe. And that should come as no surprise considering how long we’ve been living under the shadow of a pandemic. There are only so many “quarantinis” you can concoct for friends who can’t actually visit you.

If you’re going to be stuck at home, why not learn a practical skill that also happens to be delicious?

The thing is, bread making can be a daunting proposition, with every step of the process fraught with potential peril.

How could something made with just four ingredients — flour, water, yeast and salt — be so … complicated? That’s probably because we’re looking at it the way we look at just about everything in the kitchen: Follow directions, and the result will be reliably the same, whether it’s cabbage rolls or Kraft Dinner.

So why did your first foray into bread making result in a doorstopper?

According to MIT chemist Patricia Christie, who recently appeared on NPR’s “Shortwave” podcast, we have to see bread making for what it really is: a science experiment that’s conducted in the kitchen.

And like every good science experiment, at some point you may be able to declare, “It’s alive!”

That would be thanks to bread’s most fundamental element: yeast.

“The yeast is the biological leavening,” Christie explains. “So what that means is that you don’t want your bread to taste like hockey pucks. Flat and nasty. Bread is supposed to be fluffy. And the fluffiness is the gas that is produced by the yeast. Yeast is a living organism. When it eats the sugars — just like you eat sugars — it produces carbon dioxide.”

And we can thank carbon dioxide for giving bread its wonderfully bubbly texture.

So be good to your yeast. Think of it as a kind of a pet that needs to be fed. And its breakfast of champions is flour.

“Amongst the most important components of the flour are proteins, which often make up 10 to 15 percent,” notes chemistry blog Compound Interest. “These include the classes of proteins called glutenins and gliadins, which are huge molecules built up of a large number of amino acids. These are collectively referred to as gluten, a name we’re probably all familiar with.”

Kneading dough expands the network of gluten fibers, allowing yeast to spread more easily throughout. (Photo: WAYHOME studio/Shutterstock)

When you add water to that flour, you’re activating those proteins. And when you knead the dough, you help the proteins line up and interact with each other. The proteins, Compound Interest notes, will eventually form a network of gluten throughout the dough.

“Kneading the dough helps these proteins uncoil and interact with each other more strongly, strengthening the network,” the site adds.

Salt plays a role here too in strengthening those gluten bonds.

As you knead that dough, you make the gluten ever stretchier, allowing your pet yeast to feast more freely throughout the network. And as it mulches, the yeast produces those all-important carbon dioxide bubbles — the texture that will eventually make the loaf light and fluffy.

Dry yeast needs water to awaken it from hibernation. (Photo: beats1/Shutterstock)

But, like every living creature, yeast has its own quirks. It doesn’t like the cold. So if it catches a chill, it won’t be in the mood for lunch. And your dough won’t expand. Similarly, the dried yeast you buy at the grocery store needs water to activate. But that water can’t be too hot or too cold — somewhere in the range of 100 and 110 degrees Fahrenheit. Anything hotter will kill the yeast. And colder water won’t activate it at all.

(Like a laboratory, every good kitchen needs a thermometer.)

If you think yeast has to be treated very carefully when it comes to making a regular loaf of bread, wait until you get its list of demands for helping you make sourdough.

For one thing, typical store-bought yeast can’t even be bothered. You need to cultivate wild yeast for this job. Luckily, you don’t have to go out into the woods, hoping to capture some. It’s present in all flour. So just adding water and letting the mixture sit for a few days should summon those bread-making wildlings.

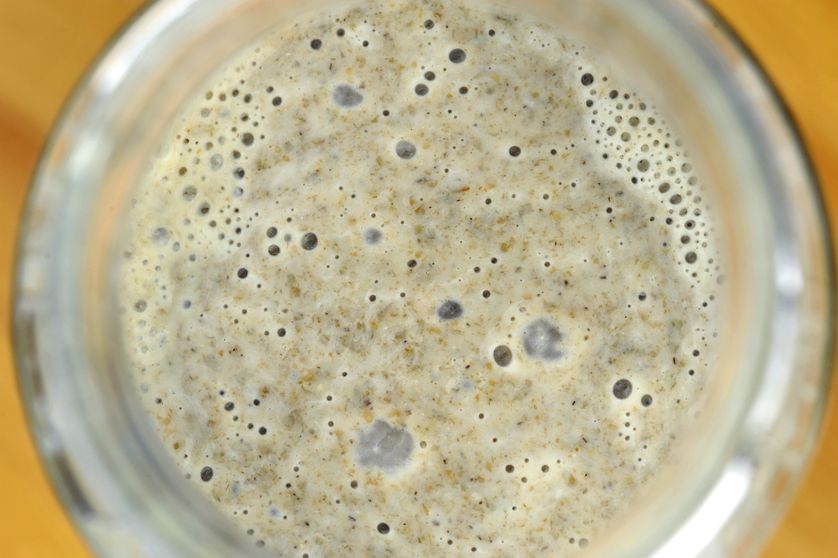

That mixture is known as sourdough starter, or simply, “mother.”

Sourdough bread grows up big and strong if it has a good ‘mother.’ (Photo: Graham Corney/Shutterstock)

“The sourdough mother is basically the master mother,” Christie tells Short Wave. “It is what is going to include all the components necessary to make more sourdough bread. Except it’s in a concentrated version.”

The idea is that when you’re going to bake some bread, you take a little bit out — mother’s little helper, if you will. That will become the basis, the hungry, bubble-making yeast for your daily dough.

But that yeast needs to be extra hungry. It needs to be put into an anaerobic state — meaning, it has burnt through its oxygen supply and is entirely producing carbon dioxide. Think bubbles.

The best way to get there is to cover mother in a bowl with plastic wrap. She’ll burn through the oxygen in the bowl in a few days — and then be downright ravenous when it’s time to meet the flour.

Of course, don’t forget to knead.

As Christie advises, you’re kneading is only done when you can stick a finger in the dough and the dough doesn’t want to let go when you try to pull it out. Congratulations! You’ve aligned those gluten fibers.

Soon, the only thing you’ll be needing is a pat of butter. Or maybe a little jam.

Related topics:

Healthy Eating

A lot of weird science goes into making bread

Think of making bread as a science experiment. But it all comes down to treating your yeast right.