EVERETT — A new state law aims to combat both climate change and hunger. It was prompted by some statistics that residents might contemplate while pulling moldy “science experiments” from the fridge or deciphering use-by dates on packaged food.

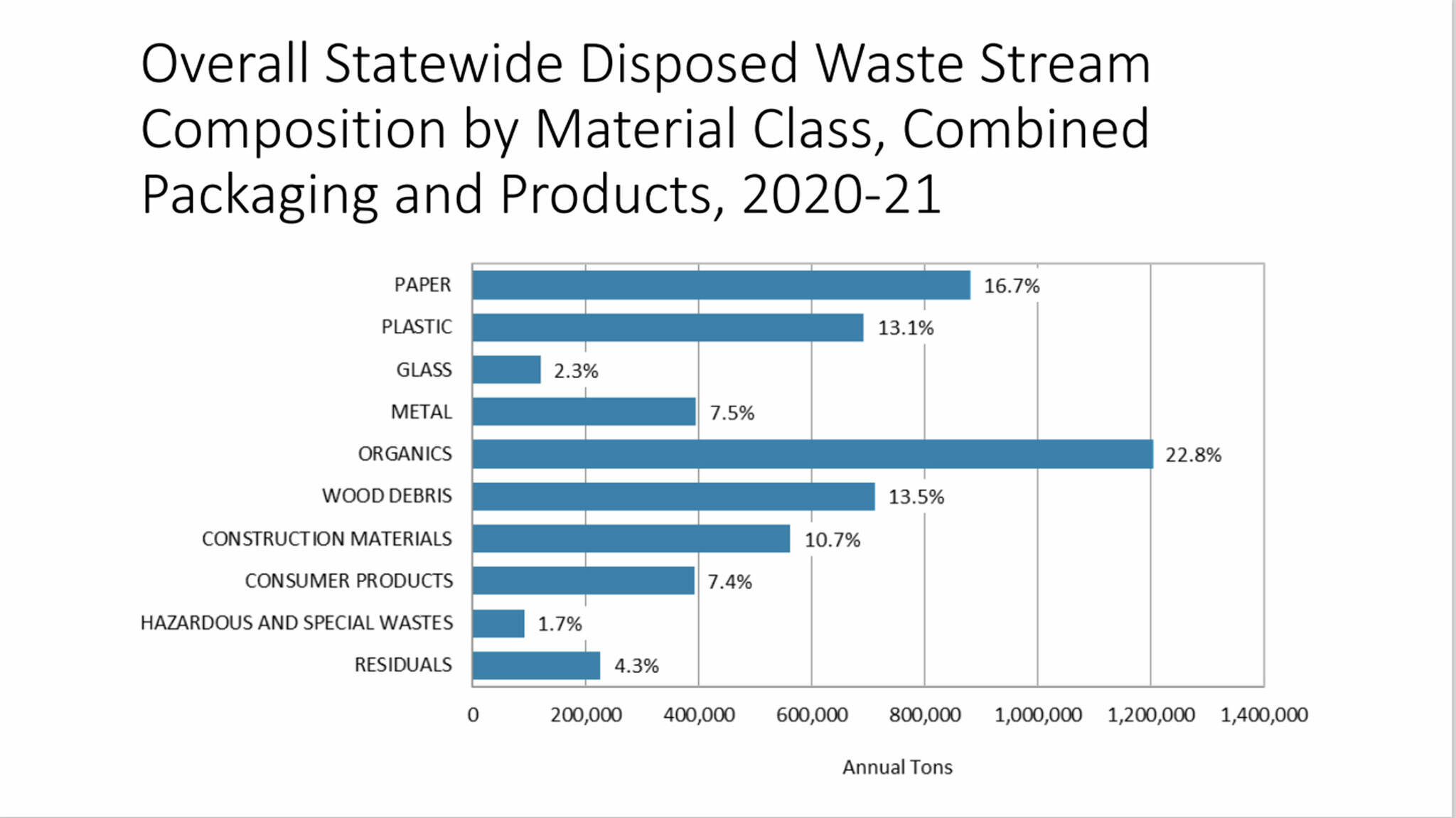

Organic matter makes up 23% of the materials going into Washington’s landfills. For residential trash alone, the figure is 33%. That is largely food waste, most of which was edible when it was tossed out.

Meanwhile, nearly one in nine residents may not know where their next meal is coming from.

Decomposing food releases methane, a heat-trapping gas that is 25 times as potent as the carbon dioxide that spews from tailpipes. Each year, the state’s landfills produce emissions equivalent to the annual exhaust of 320,000 cars.

“Food waste is the largest landfill component by tonnage. It’s heavy. And we have hungry people,” said Chery Sullivan, the Washington Department of Ecology manager who oversees implementation of the 2022 Organics Management Law.

The big, complex law will eventually change food waste collection and disposal statewide. It was passed by Democrats on a party-line vote. Costing $6.83 million over six years, it amends or adds sections to multiple existing laws. Besides Ecology, it involves the Conservation Commission, Department of Agriculture, Department of Enterprise Services, counties and cities, residential and non-residential customers.

Using 2015 as a baseline, the law aims to cut landfill-disposed organic material by 75% by 2030, and, by 2025, cut the amount of landfilled edible food by 20%. Other organic materials, including inedible food and yard waste, will be processed at composting facilities, anaerobic digesters, or used for vermiculture (worm-based composting) and emerging technologies.

The law gives state agencies through 2027 to make big changes. Ahead lies much rule-making that will affect residents, waste haulers, compost facilities, land-use plans and more.

Good Samaritan changes

Among the quickest changes will be a decrease in the amount of edible food that is thrown away because of vague labeling or legal concerns. Embedded in the Organic Management Law is a Good Samaritan Food Donation Law. Among other actions, it gives businesses more leeway to donate prepared meals without assuming liability. Food, packaged or prepared, can be sold at discount rather than given away and still merit a tax deduction.

Similar liability protections have arrived at the federal level, with passage of the Food Donation Improvement Act. Congress has yet to pass the Food Date Labeling Act, which would standardize expiration dates for perishable food.

Under Washington’s new rules, stores and distributors can contribute packaged food even if it’s beyond its “best buy” date. Only labeling such as “use by,” which is related to food safety, not flavor or appearance, means food must be thrown away. It’s an important change, said Mark Coleman, media officer for Foodline.org, which serves 17 Western Washington counties. That charity, along with Northwest Harvest, manages the relationships between grocers and food banks, and between restaurants and shelters where meals are served.

“The cardinal rule of food production is you have to have enough on hand to meet demand,” Coleman said, explaining why farmers, distributors and grocers often end up with food they can’t sell. Donating unsold inventory reduces disposal fees and provides tax deductions, he said.

Coleman’s single mom relied on food banks, he said, so he understands the hunger-fighting importance of the new law. And as a former meteorologist, he knows the peril posed by landfill emissions: “I’m always trying to get people to think about methane.”

A road map to improvements

Ecology’s Use Food Well Washington Plan is a road map to building a better food system through waste reduction. It was key to passage of the Organics Management Law and is central to its execution.

Perhaps the most significant of the 30 recommendations in the 121-page food plan is the creation of the Washington Center for Sustainable Food Management. The Organics Management Act did just that. Known simply as the Food Center, it will have a three-member Department of Ecology staff and be fully operational by 2024, Sullivan said.

The Use Food Well plan is comprehensive to say the least. It calls for actions ranging from the broad (increase markets for “imperfect” produce) to the specific (require school recess before lunch, because hungry kids leave less on their plates). It contains much data backing up the recommendations.

Some of the most significant numbers come from literal deep dives into Washington’s waste stream. To figure out how much food is wasted, Ecology hires contractors to sample and weigh trash being sent to landfills. The latest Waste Characterization Study sampled trash from sites in 10 counties in 2020 and 2021. The sites included Snohomish County’s Southwest Recycling and Transfer Station, where waste is collected before being shipped by trainload to Klickitat County’s Roosevelt Regional landfill.

As the Food Center ramps up, residents can start to see more messaging about how to keep produce from going bad. And what to do with food that does go rotten. Ideally, it is composted and turned into soil amendments — setting up a “virtuous cycle” of capturing carbon and making it useful.

Composting, large and small scale

In Snohomish County, composting is easy for those with a backyard compost pile, where bacteria will decompose most anything but animal-based leftovers. Those with a yard waste bin, for which they pay a garbage hauler, can put food scraps and other compostable materials there — including, Steve Banchero wants everyone to know, meat and bones. Just no pet poop, please.

Banchero co-owns Rubatino Refuse Removal, which serves Everett. Other regional haulers, including Waste Management, also offer large waste bins that are of no use to the ever-increasing number of apartment or condo dwellers. However, the new law will require local governments that meet specific criteria to provide source-separated organics collection to all customers by 2027.

Despite making it easier for residential customers to sort out organic waste, the law won’t require them to do it as the city of Seattle does. Seattle Public Utilities offers a 12-gallon “mini cart” for food waste. In Snohomish County, garbage hauling is done by private companies.

Haulers take organic waste to large composting facilities, including one north of Everett owned by Cedar Grove. Banchero is the company’s president. Cedar Grove has plenty of capacity to take more organics, he said. What it can always use is more customers to buy the compost created there.

“Compost is a great product,” he said.

He’s pleased that the new law requires state and local governments to look first to locally produced compost products when buying landscaping materials. The law also requires businesses and institutions that generate a lot of organic waste to start separating and properly disposing of it.

“The state has not previously said businesses separate food for composting,” Sullivan said. “Schools, hospitals, and correction facilities have an enormous amount of waste that can’t be recovered for edible consumption. The new law says we’re going to phase this in for businesses and work with local jurisdictions to phase in or build out capacity for processing.”

Many businesses, especially restaurants, have been separating organic material for years. Cedar Grove has had a commercial waste program with dedicated trucks since 2005, Banchero said.

At legislative hearings, there was no disagreement on the methane-reducing, food-saving goals of the Organic Management Act. But there was plenty of devil in the details. For example, composters are plagued by plastic produce stickers that contaminate organic waste, but the idea of banning them gave real heartburn to grocers who would have to replace them fruit-by-fruit with compostable stickers.

The idea of a plastic sticker ban was quickly dropped from the bill. Lawmakers did agree to require producers of “compostable” containers to prove their products are degradable and to clearly mark them as such.

Local anxieties, more lawmaking

There’s plenty of legislative discussion ahead when it comes to organics and recycling in general, said Heather Trim, executive director of Zero Waste Washington.

“There are 10 to 12 waste-related bills a year,” she said. Zero Waste’s 2023 legislative priorities include the Washington Recycling and Packaging Act plus bills related to plastics reduction, battery recycling and the “right to repair.”

Trim and other environmentalists lobbied enthusiastically for the Organics Management Act. Local governments, not so much. The Washington Association of Counties took a neutral stand. Policy Director Paul Jewell objected to the lack of funding to support major changes in how and where organic material goes.

“It will require huge investments in infrastructure,” Jewell said at a Senate hearing. “Planning, siting and constructing solid waste facilities is not easy, and in any event it takes years to complete,” he said. “California has had to increase fees by as much as 70% to comply” with similar requirements.

Most cities and counties have access to state and federal grants in some form, Sullivan said. Those may support things like solid waste management plan updates and public education. Ecology is working on an outreach “toolkit” to spread the word about organic waste management.

Still, Sullivan agrees that the Organic Management Act will burden local governments. Ecology will ask legislators for more grant funding to help, arguing that implementing all the Use Food Well recommendations will save $1 billion annually.

Julie Titone is an Everett writer who can be reached at julietitone@icloud.com. Her stories are supported by The Herald’s Environmental and Climate Reporting Fund.

Talk to us

- You can tell us about news and ask us about our journalism by emailing newstips@heraldnet.com or by calling 425-339-3428.

- If you have an opinion you wish to share for publication, send a letter to the editor to letters@heraldnet.com or by regular mail to The Daily Herald, Letters, P.O. Box 930, Everett, WA 98206.

- More contact information is here.