Would you notice if the cubed meat in your cup noodle wasn’t “real” meat? If you did, would you care? What if the future of our meat supply counted on it?

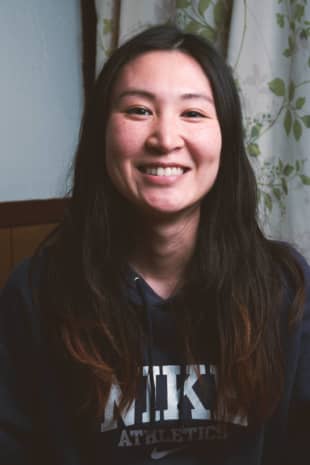

“Veganism is not for everyone,” says Yuki Hanyu, founder of IntegriCulture Inc. a Tokyo-based startup set to bring laboratory-grown foie gras to the country’s high-end restaurant market next year. This rings particularly true in Japan, where only 2.1 percent of the population is vegan, compared to 5 percent of the country’s 30 million visitors in 2018.

Internationally, veganism is on the rise, thanks in no small part to a growing awareness of meat’s negative environmental impact. Globally, livestock is responsible for 14.5 percent of greenhouse gas emissions according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. At current levels of consumption, the Paris Agreement’s global emission reduction targets won’t be met, yet the sector is seeing unprecedented growth.

The global picture is Japan’s story writ large. In 2005, meat overtook fish as the main protein source in the Japanese diet. Since then, demand has outpaced domestic production, with the domestic meat industry predicted to reach ¥2.6 trillion (about $23 billion) by 2023. In Japan, which has a food self-sufficiency rate of only 37 percent, this has not escaped the government’s notice. In 2019, it formed a “Vege Council” made up of politicians and representatives from vegan-related groups and nonpolitical organizations and contributed to a $2.7 million investment in “cellular agriculture” — aka lab-grown, or cultured, meat.

Making ‘meat’ mainstream

Cultured meat, like that manufactured by IntegriCulture, is made from cells extracted from an animal and grown on a culture medium — a mixture of water, salt, amino acids, vitamins, minerals and nutrients that cells use as food. Manufacturers claim it tastes just like the “real thing,” and can be produced on a fraction of the land with a fraction of the energy.

Meanwhile, according to Vege Council member and co-founder of Tokyo Vegan Meetup Nadia McKechnie, the Council has primarily focused on educating tourist-oriented businesses about the specific requirements for vegetarian and vegan diets. Done well, spreading awareness of the need to cater to dietary restrictions could help the nation both profit from the global multibillion-dollar plant-based market and meet its climate goals.

Cellular meat, too, has yet to widely register on Japan’s public radar where, Hanyu says, “acceptability in Japan comes out much the same as it does in U.S. or European studies.”

In a joint 2019 poll from Nissin Foods Holdings and Hirosaki University, when respondents who had little knowledge of the industry were asked “Would you want to try cellular meat?” only 6 percent replied “strongly agree,” 21 percent said “somewhat agree” and 44 percent either “somewhat” or “strongly” disagreed (29 percent had no opinion). But among people who already had some working knowledge of cellular meat, the percentage of those who definitely wanted to try it rose to 20 percent.

But this is not enough for Hanyu, who says “surveys like this have been done so many times everywhere, but they’re missing one critical thing: the actual product.”

Cultured meat’s onward creep may have eluded Japanese consumers, but it’s the flavor of the moment for global businesses, governments and investors. It’s even received significant attention from meat industry megaliths, such as Tyson Foods, the world’s second-largest meat-producing company.

In Japan, beef producer Toriyama Chikusan Shokuhin, meat and seafood supplier Awano Food Group and the aforementioned Nissin are just a few of the companies invested in the industry. Others, such as Otsuka Foods, Mitsui & Co. and Nishimoto Co., are putting their weight behind developing “novel vegan meat replacements” made from plants, in the vein of popular products such as the Impossible Burger.

Even as corporate-scale research and development ticks along behind the scenes, Hanyu is hell-bent on making the product mainstream.

**media[4853]**

A home-grown movement

By day, IntegriCulture’s Hanyu is a shrewd CEO, but by night he lets his passion for cellular agriculture rip. Alongside IntegriCulture, he runs the Shojinmeat Project, a nonprofit intent on getting cellular agriculture in the hands of many. The ambition: Increase consumer acceptability. The strategy: Tap into Japan’s deep love of anime.

Shojinmeat hosts open-access weekly “meet-ups” and circulates the recipe for cell-grown meat anyone can make at home in manga form.

“As far as I know, the best way to reach Generation Z in East Asia, and there’s 500 million of them, is anime and manga,” Hanyu says. “It’s about conveying the joy of DIY biohacking and imaginative thinking.”

While the meet-ups play host to many young science buffs and manga fans, it also attracted government officials from the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST). After six months of attendance, JST earmarked $20 million for various cell-based meat projects. Hanyu puts this down to the relaxed nature of the meet-up, which makes space for imaginative, expansive thinking.

“Only a tiny fraction (of funding) went into IntegriCulture, but the most significant thing is it’s the first multimillion dollar piece of government funding specifically targeted at cell-based meat with commercialization insight,” Hanyu says. “It’s not just academic.”

The University of Cambridge chemistry doctorate first set up the bioreactor needed to grow cells between his parents’ toaster and microwave. “Conventionally, big companies and universities drive the development of new technologies,” he says. “I thought, ‘That’s boring, it’s funnier if a citizens movement leads.’”

Hanyu sees a future in which IntegriCulture’s CulNet System bioreactors exist in the home, the community and on an industrial scale. Owners will be able to “design” their own meat, altering the taste and nutrient profile to create signature dishes.

Although Hanyu acknowledges the increasing interest in low-meat diets, he doesn’t feel it’s a “necessary option for everyone.” Especially in Japan where, he cautions, “vegans are perceived as arrogant. They give the impression they are morally superior.”

Yuki Daniels, proprietor of Hallogallo, Tokyo’s first vegan bar, thinks otherwise. She’s not sure that Japan needs a novel meat supply: She’d rather vegetables get decent PR. Where Daniels does agree with Hanyu is that it’s hard to go against the grain, especially with Japan’s culture of sharing dishes.

When Daniels and her partner go out with friends, they often forgo food for ease. However, this isn’t an option when dining with colleagues, explains current vegetarian and aspiring vegan, Yumi Fujisawa.

“When you say you’re a vegetarian, people are like ‘Errrr,’” Fujisawa says. “They have to find a restaurant with a vegetarian menu. … I was a secretary for five years and had to go to many dinner meetings with my boss. I wasn’t able to say (I was vegetarian) because that’s not supposed to happen. People wouldn’t want to take me to the restaurant.”

McKechnie is also concerned by the number of people in Japan who struggle to tell others they’re vegan. It gives the illusion that there’s little domestic demand, meaning the industry doesn’t respond.

“There are Japanese people who don’t want to eat meat, but they’re in the closet,” McKechnie says. “People don’t know that there’s a huge market in Japan. No one talks about veganism in the press, there’s little data and few products.”

Growth potential

Taken together, Japan’s nascent vegan movement, desire for meat and willingness to experiment with new technology stand Hanyu in good stead. Add land shortages and continued funding interest to the mix and the scene may be set for his desired future. But the obstacles to cultured meat are as real in Japan as they are elsewhere. Even as cost is expected to drop and acceptability to rise, it remains to be seen if the technology can deliver at scale and compete with novel meat replacements. In the short term, Japan will need to focus on diversifying its protein sources.

Hanyu’s not daunted: In fact, he agrees with industry experts who hold that novel vegan meat replacements will support the long-term transition toward cultured meat. “In three years things won’t look very different from today,” he says. “In 10 years, there’ll be many more plant-based alternatives. Cell-based will be less than .1 percent of the market. (But) after that, change is predicted at pace.”